Every minute, on average, at least one person dies in a crash. If you read this article from start to finish, 30 or more deaths will have occurred across the globe by the time you are done. Auto accidents will also injure at least 10 million people this year, two or three million of them seriously.

All told, the hospital bills, damaged property, and other costs will add up to 1-3 percent of the world’s gross domestic product, according to the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. For the United States alone, the tally will amount to roughly US $200 billion. And, of course, the losses that matter most are not even captured by these statistics, because there’s no way to put a dollar value on them.

Engineers have been chipping away at these staggering numbers for a long time. Air bags and seat belts save tens of thousands of people a year. Supercomputers now let designers create car frames and bodies that protect the people inside by absorbing as much of the energy of a crash as possible. As a result, the number of fatalities per million miles of vehicle travel has decreased. But the ultimate solution, and the only one that will save far more lives, limbs, and money, is to keep cars from smashing into each other in the first place.

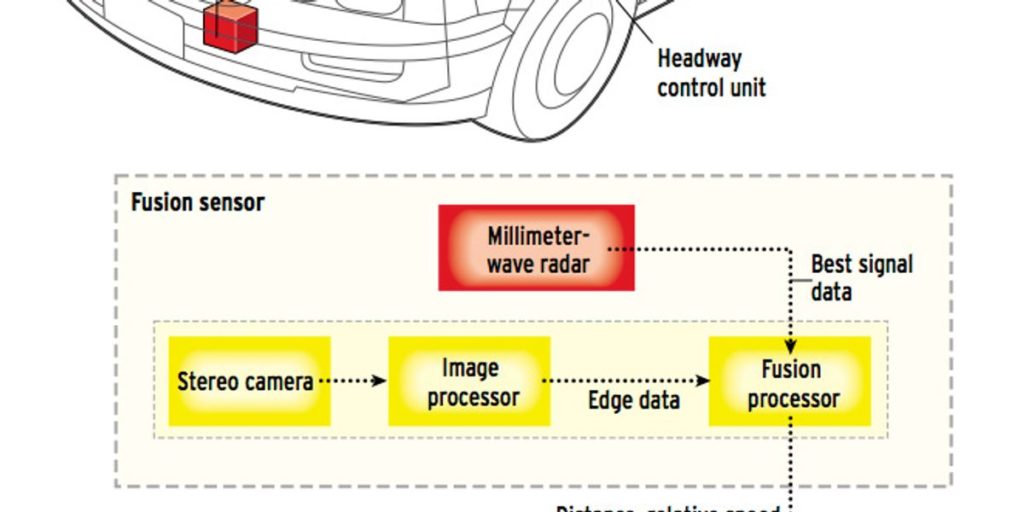

That is exactly what engineers in the United States, Europe, and Japan are trying to do. They are applying advanced microprocessors, radars, high-speed ICs, and signal-processing chips and algorithms in RandD programs that mark an about-face in the automotive industry: from safety systems that kick in after an accident occurs, attempting to minimize injury and damage, to ones that prevent collisions altogether.

The first collision-avoidance features are already on the road, as pricey adaptive cruise control options on a small group of luxury cars. Over the next few years, these systems will grow more capable and more widely available, until they become standard equipment on luxury vehicles. Meanwhile, researchers will be bringing the first cooperative safety systems to market. These will raise active safety technology to the next level, enabling vehicles to communicate and coordinate responses to avoid collisions. Note that to avoid liability claims in the event of collisions between cars equipped with adaptive cruise control systems, manufacturers of these systems and the car companies that use them are careful not to refer to them as safety devices. Instead, they are being marketed as driver aids, mere conveniences made possible by new technologies.

Further in the future, developments by private research groups and publicly funded entities such as the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) Joint Program Office, and Japan’s Advanced Cruise-Assist Highway System Research Association, may make driving a completely automated experience. Communication among sensors and processors embedded not only in vehicles but in roads, signs, and guard rails are expected to let cars race along practically bumper to bumper at speeds above 100 km/h while passengers snooze, read, or watch television.