Despite this initial dominance, by 1986 the IBM PC was becoming an also-ran. And in 2005, the Chinese computer maker Lenovo Group purchased IBM’s PC business.

What occurred between IBM’s wildly successful entry into the personal computer business and its inglorious exit nearly a quarter century later? From IBM’s perspective, a new and vast market quickly turned into an ugly battleground with many rivals. The company stumbled badly, its bureaucratic approach to product development no match for a fast-moving field. Over time, it became clear that the sad story of the IBM PC mirrored the decline of the company.

At the outset, though, things looked rosy.

How the personal computer revolution was launched

Contents

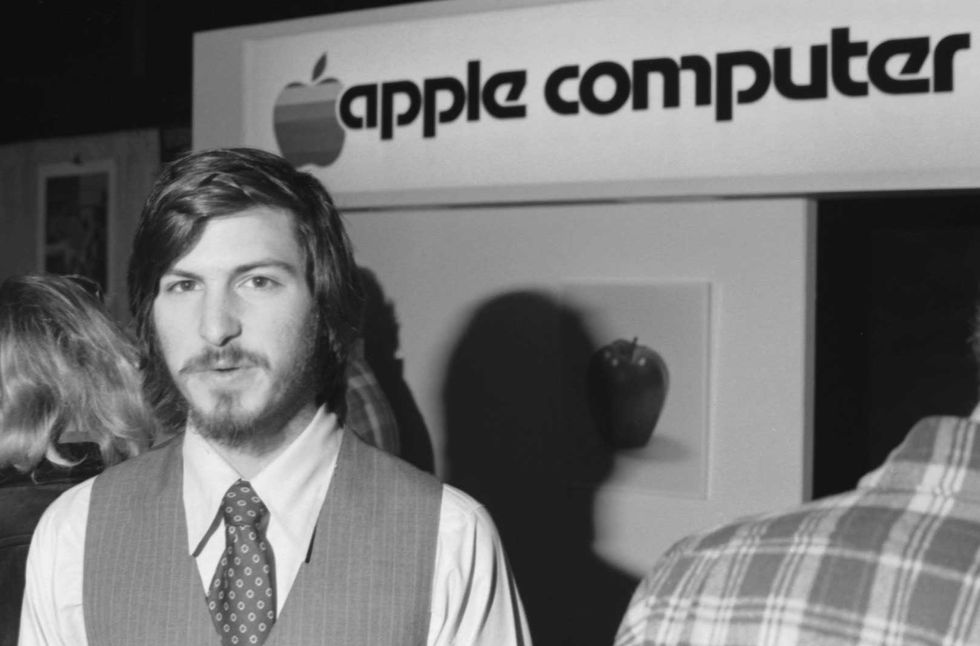

IBM did not invent the desktop computer. Most historians agree that the personal computer revolution began in April 1977 at the first West Coast Computer Faire. Here, Steve Jobs introduced the Apple II, with a price tag of US $1,298 (about $5,800 today), while rival Commodore unveiled its PET. Both machines were designed for consumers, not just hobbyists or the technically skilled. In August, Tandy launched its TRS-80, which came with games. Indeed, software for these new machines was largely limited to games and a few programming tools.

Apple cofounder Steve Jobs unveiled the Apple II at the West Coast Computer Faire in April 1977.

Tom Munnecke/Getty Images

IBM’s large commercial customers faced the implications of this emerging technology: Who would maintain the equipment and its software? How secure was the data in these machines? And what was IBM’s position: Should personal computers be taken seriously or not? By 1980, customers in many industries were telling their IBM contacts to enter the fray. At IBM plants in San Diego, Endicott, N.Y, and Poughkeepsie, N.Y., engineers were forming hobby clubs to learn about the new machines.

The logical place to build a small computer was inside IBM’s General Products Division, which focused on minicomputers and the successful typewriter business. But the division had no budget or people to allocate to another machine. IBM CEO Frank T. Cary decided to fund the PC’s development out of his own budget. He turned to William “Bill” Lowe, who had given some thought to the design of such a machine. Lowe reported directly to Cary, bypassing IBM’s complex product-development bureaucracy, which had grown massively during the creation of the System/360 and S/370. The normal process to get a new product to market took four or five years, but the incipient PC market was moving too quickly for that.

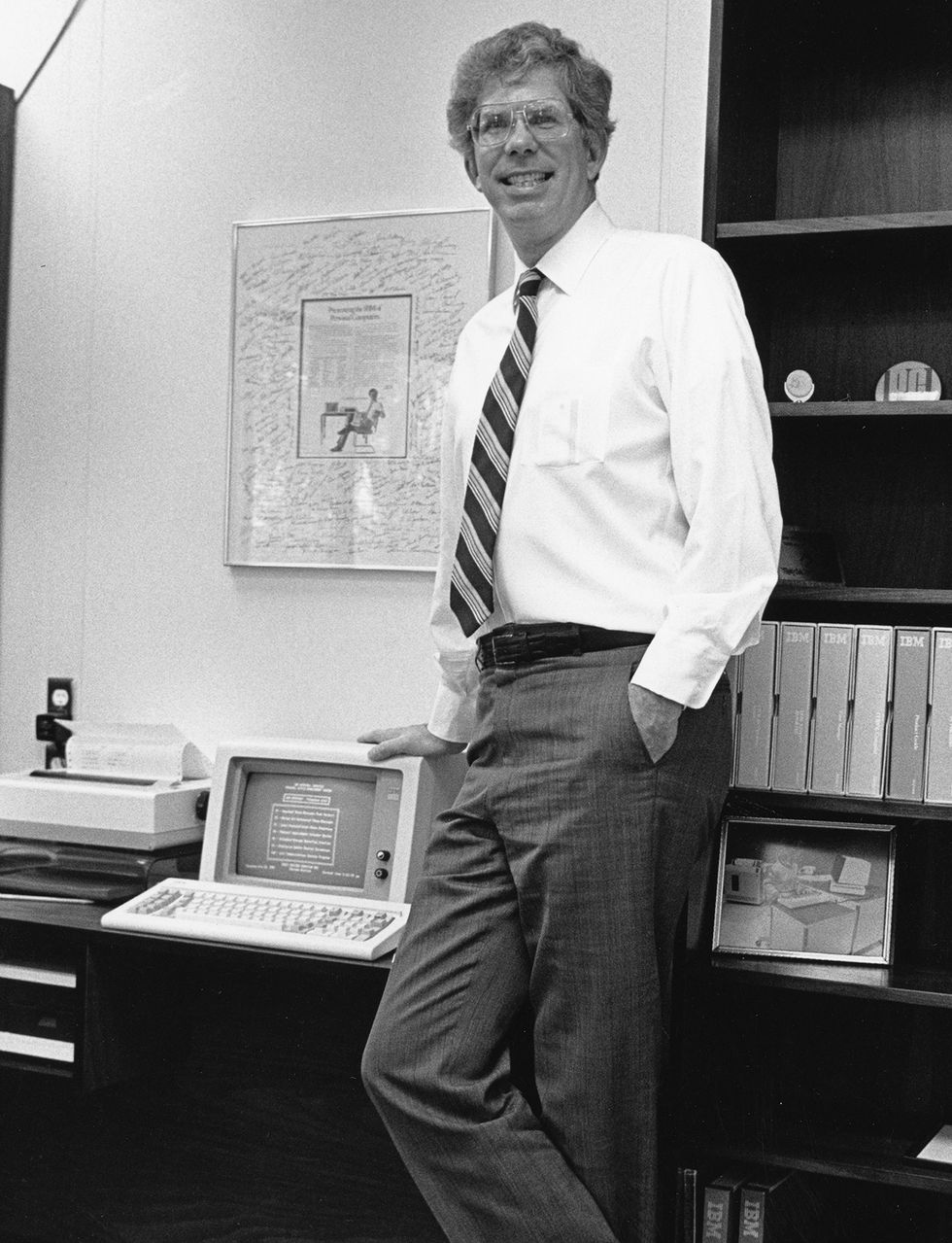

IBM CEO Frank T. Cary authorized a secret initiative to develop a personal computer outside of Big Blue’s product-development process.

IBM

Cary asked Lowe to come back in several months with a plan for developing a machine within a year and to find 40 people from across IBM and relocate them to Boca Raton, Fla.

Lowe’s plan for the PC called for buying existing components and software and bolting them together into a package aimed at the consumer market. There would be no homegrown operating system or IBM-made chips. The product also had to attract corporate customers, although it was unclear how many of those there would be. Mainframe salesmen could be expected to ignore or oppose the PC, so the project was kept reasonably secret.

A friend of Lowe’s, Jack Sams, was a software engineer who vaguely knew Bill Gates, and he reached out to the 24-year-old Gates to see if he had an operating system that might work for the new PC. Gates had dropped out of Harvard to get into the microcomputer business, and he ran a 31-person company called Microsoft. While he thought of programming as an intellectual exercise, Gates also had a sharp eye for business.

In July 1980, the IBMers met with Gates but were not greatly impressed, so they turned instead to Gary Kildall, president of Digital Research, the most recognized microcomputer software company at the time. Kildall then made what may have been the business error of the century. He blew off the blue-suiters so that he could fly his airplane, leaving his wife—a lawyer—to deal with them. The meeting went nowhere, with too much haggling over nondisclosure agreements, and the IBMers left. Gates was now their only option, and he took the IBMers seriously.

The normal process to get a new IBM product to market took four or five years, but the incipient PC market was moving too quickly for that.

That August, Lowe presented his plan to Cary and the rest of the management committee at IBM headquarters in Armonk, N.Y. The idea of putting together a PC outside of IBM’s development process disturbed some committee members. The committee knew that IBM had previously failed with its own tiny machines—specifically the Datamaster and the 5110—but Lowe was offering an alternative strategy and already had Cary’s support. They approved Lowe’s plan.

Lowe negotiated terms, volumes, and delivery dates with suppliers, including Gates. To meet IBM’s deadline, Gates concluded that Microsoft could not write an operating system from scratch, so he acquired one called QDOS (“quick and dirty operating system”) that could be adapted. IBM wanted Microsoft, not the team in Boca Raton, to have responsibility for making the operating system work. That meant Microsoft retained the rights to the operating system. Microsoft paid $75,000 for QDOS. By the early 1990s, that investment had boosted the firm’s worth to $27 billion. IBM’s strategic error in not retaining rights to the operating system went far beyond that $27 billion; it meant that Microsoft would set the standards for the PC operating system. In fairness to IBM, nobody thought the PC business would become so big. Gates said later that he had been “lucky.”

Back at Boca Raton, the pieces started coming together. The team designed the new product, lined up suppliers, and were ready to introduce the IBM Personal Computer just a year after gaining the management committee’s approval. How was IBM able to do this?

Much credit goes to Philip Donald Estridge. An engineering manager known for bucking company norms, Estridge turned out to be the perfect choice to ram this project through. He wouldn’t show up at product-development review meetings or return phone calls. He made decisions quickly and told Lowe and Cary about them later. He staffed up with like-minded rebels, later nicknamed the “Dirty Dozen.” In the fall of 1980, Lowe moved on to a new job at IBM, so Estridge was now in charge. He obtained 8088 microprocessors from Intel, made sure Microsoft kept the development of DOS secret, and quashed rumors that IBM was building a system. The Boca Raton team put in long hours and built a beautiful machine.

The IBM PC was a near-instant success

The big day came on 12 August 1981. Estridge wondered if anyone would show up at the Waldorf Astoria. After all, the PC was a small product, not in IBM’s traditional space. Some 100 people crowded into the hotel. Estridge described the PC, had one there to demonstrate, and answered a few questions.

The IBM PC was aimed squarely at the business market, which compelled other computer makers to follow suit.

IBM

Meanwhile, IBM salesmen had received packets of materials the previous day. On 12 August, branch managers introduced the PC to employees and then met with customers to do the same. Salesmen weren’t given sample machines. Along with their customers, they collectively scratched their heads, wondering how they could use the new computer. For most customers and IBMers, it was a new world.

Nobody predicted what would happen next. The first shipments began in October 1981, and in its first year, the IBM PC generated $1 billion in revenue, far exceeding company projections. IBM’s original manufacturing forecasts called for 1 million machines over three years, with 200,000 the first year. In reality, customers were buying 200,000 PCs per month by the second year.

Those who ordered the first PCs got what looked to be something pretty clever. It could run various software packages and a nice collection of commercial and consumer tools, including the accessible BASIC programming language. Whimsical ads for the PC starred Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp and carried the tag line “A Tool for Modern Times.” People could buy the machines at ComputerLand, a popular retail chain in the United States. For some corporate customers, the fact that IBM now had a personal computing product meant that these little machines were not some crazy geek-hippie fad but in fact a new class of serious computing. Corporate users who did not want to rely on their company’s centralized data centers began turning to these new machines.

Estridge and his team were busy acquiring games and business software for the PC. They lined up Lotus Development Corp. to provide its 1-2-3 spreadsheet package; other software products followed from multiple suppliers. As developers began writing software for the IBM PC, they embraced DOS as the industry standard. IBM’s competitors, too, increasingly had to use DOS and Intel chips. And Cary’s decision to avoid the product-development bureaucracy had paid off handsomely.

IBM couldn’t keep up with rivals in the PC market

Encouraged by their success, the IBMers in Boca Raton released a sequel to the PC in early 1983, called the XT. In 1984 came the XT’s successor, the AT. That machine would be the last PC designed outside IBM’s development process. John Opel, who had succeeded Cary as CEO in January 1981, endorsed reining in the PC business. During his tenure, Opel remained out of touch with the PC and did not fully understand the significance of the technology.

We could conclude that Opel did not need to know much about the PC because business overall was outstanding. IBM’s revenue reached $29 billion in 1981 and climbed to $46 billion in 1984. The company was routinely ranked as one of the best run. IBM’s stock more than doubled, making IBM the most valuable company in the world.

The media only wanted to talk about the PC. On its 3 January 1983 cover, Time featured the personal computer, rather than its usual Man of the Year. IBM customers, too, were falling in love with the new machines, ignoring IBM’s other lines of business—mainframes, minicomputers, and typewriters.

Don Estridge was the right person to lead the skunkworks in Boca Raton, Fla., where the IBM PC was built.

IBM

On 1 August 1983, Estridge’s skunkworks was redesignated the Entry Systems Division (ESD), which meant that the PC business was now ensnared in the bureaucracy that Cary had bypassed. Estridge’s 4,000-person group mushroomed to 10,000. He protested that Corporate had transferred thousands of programmers to him who knew nothing about PCs. PC programmers needed the same kind of machine-software knowledge that mainframe programmers in the 1950s had; both had to figure out how to cram software into small memories to do useful work. By the 1970s, mainframe programmers could not think small enough.

Estridge faced incessant calls to report on his activities in Armonk, diverting his attention away from the PC business and slowing development of new products even as rivals began to speed up introduction of their own offerings. Nevertheless, in August 1984, his group managed to release the AT, which had been designed before the reorganization.

But IBM blundered with its first product for the home computing market: the PCjr (pronounced “PC junior”). The company had no experience with this audience, and as soon as IBM salesmen and prospective customers got a glimpse of the machine, they knew something had gone terribly wrong.

Unlike the original PC, the XT, and the AT, the PCjr was the sorry product of IBM’s multilayered development and review process. Rumors inside IBM suggested that the company had spent $250 million to develop it. The computer’s tiny keyboard was scornfully nicknamed the “Chiclet keyboard.” Much of the PCjr’s software, peripheral equipment, memory boards, and other extensions were incompatible with other IBM PCs. Salesmen ignored it, not wanting to make a bad recommendation to customers. IBM lowered the PCjr’s price, added functions, and tried to persuade dealers to promote it, to no avail. ESD even offered the machines to employees as potential Christmas presents for a few hundred dollars, but that ploy also failed.

IBM’s relations with its two most important vendors, Intel and Microsoft, remained contentious. Both Microsoft and Intel made a fortune selling IBM’s competitors the same products they sold to IBM. Rivals figured out that IBM had set the de facto technical standards for PCs, so they developed compatible versions they could bring to market more quickly and sell for less. Vendors like AT&T, Digital Equipment Corp., and Wang Laboratories failed to appreciate that insight about standards, and they suffered. (The notable exception was Apple, which set its own standards and retained its small market share for years.) As the prices of PC clones kept falling, the machines grew more powerful—Moore’s Law at work. By the mid-1980s, IBM was reacting to the market rather than setting the pace.

For some corporate customers, the fact that IBM now had a personal computing product meant that these little machines were not some crazy geek-hippie fad but were in fact a new class of serious computing.

Estridge was not getting along with senior executives at IBM, particularly those on the mainframe side of the house. In early 1985, Opel made Bill Lowe head of the PC business.

Then disaster struck. On 2 August 1985, Estridge, his wife, Mary Ann, and a handful of IBM salesmen from Los Angeles boarded Delta Flight 191 headed to Dallas. Over the Dallas airport, 700 feet off the ground, a strong downdraft slammed the plane to the ground, killing 137 people including the Estridges and all but one of the other IBM employees. IBMers were in shock. Despite his troubles with senior management, Estridge had been popular and highly respected. Not since the death of Thomas J. Watson Sr. nearly 30 years earlier had employees been so stunned by a death within IBM. Hundreds of employees attended the Estridges’ funeral. The magic of the PC may have died before the airplane crash, but the tragedy at Dallas confirmed it.

More missteps doomed the IBM PC and its OS/2 operating system

While IBM continued to sell millions of personal computers, over time the profit on its PC business declined. IBM’s share of the PC market shrank from roughly 80 percent in 1982–1983 to 20 percent a decade later.

Meanwhile, IBM was collaborating with Microsoft on a new operating system, OS/2, even as Microsoft was working on Windows, its replacement for DOS. The two companies haggled over royalty payments and how to work on OS/2. By 1987, IBM had over a thousand programmers assigned to the project and to developing telecommunications, costing an estimated $125 million a year.

OS/2 finally came out in late 1987, priced at $340, plus $2,000 for additional memory to run it. By then, Windows had been on the market for two years and was proving hugely popular. Application software for OS/2 took another year to come to market, and even then the new operating system didn’t catch on. As the business writer Paul Carroll put it, OS/2 began to acquire “the smell of failure.”

Known to few outside of IBM and Microsoft, Gates had offered to sell IBM a portion of his company in mid-1986. It was already clear that Microsoft was going to become one of the most successful firms in the industry. But Lowe declined the offer, making what was perhaps the second-biggest mistake in IBM’s history up to then, following his first one of not insisting on proprietary rights to Microsoft’s DOS or the Intel chip used in the PC. The purchase price probably would have been around $100 million in 1986, an amount that by 1993 would have yielded a return of $3 billion and in subsequent decades orders of magnitude more.

In fairness to Lowe, he was nervous that such an acquisition might trigger antitrust concerns at the U.S. Department of Justice. But the Reagan administration was not inclined to tamper with the affairs of large multinational corporations.

Gates offered to sell IBM a portion of Microsoft in mid-1986. But Lowe declined the offer, making what was perhaps the second-biggest mistake in IBM’s history up to then.

More to the point, Lowe, Opel, and other senior executives did not understand the PC market. Lowe believed that PCs, and especially their software, should undergo the same rigorous testing as the rest of the company’s products. That meant not introducing software until it was as close to bugproof as possible. All other PC software developers valued speed to market over quality—better to get something out sooner that worked pretty well, let users identify problems, and then fix them quickly. Lowe was aghast at that strategy.

Salesmen came forward with proposals to sell PCs in bulk at discounted prices but got pushback. The sales team I managed arranged to sell 6,000 PCs to American Standard, a maker of bathroom fixtures. But it took more than a year and scores of meetings for IBM’s contract and legal teams to authorize the terms.

Lowe’s team was also slow to embrace the faster chips that Intel was producing, most notably the 80386. The new Intel chip had just the right speed and functionality for the next generation of computers. Even as rivals moved to the 386, IBM remained wedded to the slower 286 chip.

As the PC market matured, the gold rush of the late 1970s and early 1980s gave way to a more stable market. A large software industry grew up. Customers found the PC clones, software, and networking tools to be just as good as IBM’s products. The cost of performing a calculation on a PC dropped so much that it was often significantly cheaper to use a little machine than a mainframe. Corporate customers were beginning to understand that economic reality.

Opel retired in 1986, and John F. Akers inherited the company’s sagging fortunes. Akers recognized that the mainframe business had entered a long, slow decline, the PC business had gone into a more rapid fall, and the move to billable services was just beginning. He decided to trim the ranks by offering an early retirement program. But too many employees took the buyout, including too many of the company’s best and brightest.

In 1995, IBM CEO Louis V. Gerstner Jr. finally pulled the plug on OS/2. It did not matter that Microsoft’s software was notorious for having bugs or that IBM’s was far cleaner. As Gerstner noted in his 2002 book, “What my colleagues seemed unwilling or unable to accept was that the war was already over and was a resounding defeat—90 percent market share for Windows to OS/2’s 5 percent or 6 percent.”

The end of the IBM PC

IBM soldiered on with the PC until Samuel J. Palmisano, who once worked in the PC organization, became CEO in 2002. IBM was still the third-largest producer of personal computers, including laptops, but PCs had become a commodity business, and the company struggled to turn a profit from those products. Palmisano and his senior executives had the courage to set aside any emotional attachments to their “Tool for Modern Times” and end it.

In December 2004, IBM announced it was selling its PC business to Lenovo for $1.75 billion. As the New York Times explained, the sale “signals a recognition by IBM, the prototypical American multinational, that its own future lies even further up the economic ladder, in technology services and consulting, in software and in the larger computers that power corporate networks and the Internet. All are businesses far more profitable for IBM than its personal computer unit.”

As soon as IBM salesmen and prospective customers got a glimpse of the IBM PCjr, they knew something had gone terribly wrong.

IBM already owned 19 percent of Lenovo, which would continue for three years under the deal, with an option to acquire more shares. The head of Lenovo’s PC business would be IBM senior vice president Stephen M. Ward Jr., while his new boss would be Lenovo’s chairman, Yang Yuanquing. Lenovo got a five-year license to use the IBM brand on the popular Thinkpad laptops and PCs, and to hire IBM employees to support existing customers in the West, where Lenovo was virtually unknown. IBM would continue to design new laptops for Lenovo in Raleigh, N.C. Some 4,000 IBMers already working in China would switch to Lenovo, along with 6,000 in the United States.

The deal ensured that IBM’s global customers had familiar support while providing a stable flow of maintenance revenue to IBM for five years. For Lenovo, the deal provided a high-profile partner. Palmisano wanted to expand IBM’s IT services business to Chinese corporations and government agencies. Now the company was partnered with China’s largest computer manufacturer, which controlled 27 percent of the Chinese PC market. The deal was one of the most creative in IBM’s history. And yet it remained for many IBMers a sad close to the quarter-century chapter of the PC.

This article is based on excerpts from IBM: The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon (MIT Press, 2019).

Part of a continuing series looking at photographs of historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the August 2021 print issue as “A Tool for Modern Times.”