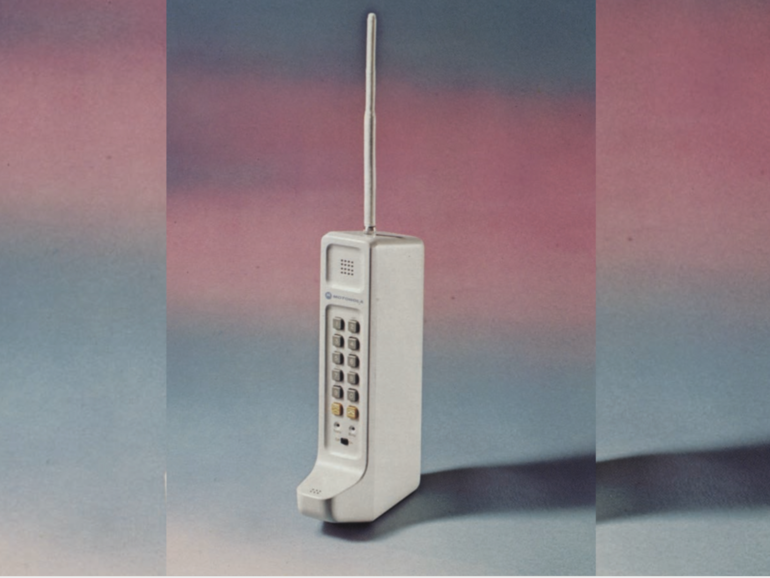

Cooper, left, showing FCC commissioner Benjamin Hooks the first cell phone, the DynaTAC, in 1973. “There was unanimity within Motorola regarding AT&T: they could not be allowed to extend their monopoly […] We had to beat them; we had to beat the monopoly.”

Motorola, Inc., Legacy Archives Collection. Reproduced with permission.

The year is 1959. A young executive is on a guerrilla reconnaissance mission for his employer, a scrappy electronics company. He approaches the gleaming headquarters building of his largest customer, an implacable firm, the biggest in the world, with one million employees. The bosses in the giant firm treat him like a poor relation, a pauper begging for a gold coin. One of the bosses is even named “King.”

The young executive is Marty Cooper, an employee of the Motorola corporation, the client is AT&T, then the world’s biggest company, and the mission is to find out what AT&T’s next big project is and how Moto can clinch the deal.

You just can’t make this stuff up. Cooper’s memoir of his years at Moto, Cutting the cord: The creator of the cell phone speaks out, which goes on sale Tuesday, reads like the best Netflix show you could ever want to see.

You can feel the Jet Age at mid-century as Cooper approaches the modernist, Eero Saarinen-designed glass box building in Holmdel, New Jersey that houses Bell Labs, a division of AT&T, and at that time, the intellectual center of the technology universe.

You can feel the arrogance of the old guard as a director at the Lab, Dr. King Edward Gould, tells Cooper in no uncertain terms how insignificant Motorola is to AT&T. The brains of a new wireless service AT&T is setting up will be made by another vendor. Motorola’s contribution, the radio transceiver, “is incidental, relatively unimportant,” he says. “We won’t have ‘the tail wagging the dog’,” he warns Cooper.

AT&T is the bad guy in this story, and what Gould and other Bell Heads couldn’t possibly have imagined, and wouldn’t have believed, is that in twenty five years, the Bell system would be broken up by court order, and the old landline regime would be beginning its long descent as cellular took over. This is a tale about empires crumbling and new worlds emerging, and it’s breathtaking.

The battle for the first cell phone turned into a battle for world views. AT&T had been selling car radios, two-way walkie-talkies of a sort, since 1946 and only had 30,000 users. When in 1969 it asked the FCC to give it exclusive use of spectrum to start a nationwide wireless phone system, AT&T told the government it was a minor project. Cellular would be just an extension of car radio. Most people would never abandon their trusty landline phones.

Cooper thought differently. He had seen the effect of equipping Chicago’s police department with the first radios they could wear on their belts. He had helped to build the first pager network for doctors and nurses at Mount Sinai hospital in New York City. He knew people wanted to possess these new communications devices in a very intense, personal way.

“For the Bell System, everything was seen as an adjunct to the wired system, and for mobile phones that adjunct extended only as far as the car trunk,” writes Cooper. “For me and Motorola, the vision and objective were driven by a different logic— that of radio and the freedom it implied.”

He would later crystallize his world view in a form he repeats throughout the book: “People connect with people, not places,” something that AT&T couldn’t see because of AT&T’s investment in its monopoly.

Amazingly, Cooper convinced his bosses to put everything behind the design of a phone that would arm AT&T’s competitors, the proverbial bet-the-company move. Like Cooper, his bosses realized it wouldn’t be the best thing if AT&T’s monopoly was extended to a new realm.

“There was unanimity within Motorola regarding AT&T: they could not be allowed to extend their monopoly […] We had to beat them; we had to beat the monopoly.”

In just three months, Cooper, who was then head of “systems operations” in the communications division at Motorola, got key engineers throughout the company to drop all their other work and build a prototype to show the FCC.

From his position as an engineer in the trenches rallying other engineers, Cooper offers us exquisitely detailed technology descriptions that no journalist would ever accomplish:

It needed to be full duplex: callers needed to be able to talk and listen at the same time. It wasn’t merely an extension of two-way radio service. To do this we’d need a radio frequency power amplifier that could produce a watt of energy continuously and reliably at 900 MHz. Such a device did not yet exist […] The radio receiver needed to be extremely sensitive to extract the impossibly weak 900 MHz signal from the air. And we needed a tri-selector, the device that made full duplex possible in the IMTS radiotelephone, except that our tri-selector needed to be miniature […] The new phone also needed to use hundreds of mobile radio channels, but we had never built a two-way radio with more than a half dozen channels […] This was 1972; there were no large-scale integrated circuits. We would need to use a large number of small-scale ones. Fortunately, our engineers had already been working on designing a new generation of integrated circuits. That work was still developmental but, hopefully, they could rush something out of the lab.

Cooper crystalizes the technology pivot point that put Moto ahead of everyone else including AT&T. Until that time, radio systems like the walkie-talkie and the handy-talkie had sent signals in a narrow range of pre-set frequencies to avoid interference.

Cooper and his team realized that if people were going to communicate in denser urban environments, the phone would have to dial down its power so that it wouldn’t drown out other people on their phones nearby who were also using the spectrum. Motorola’s first patent on cellular, with Cooper as lead inventor, includes this power management feature.

It was a stunning insight into the future use of something that didn’t even exist. Cooper was asking his team to envision not just a new kind of technology, but the details of how it would function in a new world it was about to make possible. Talk about “the vision thing”!

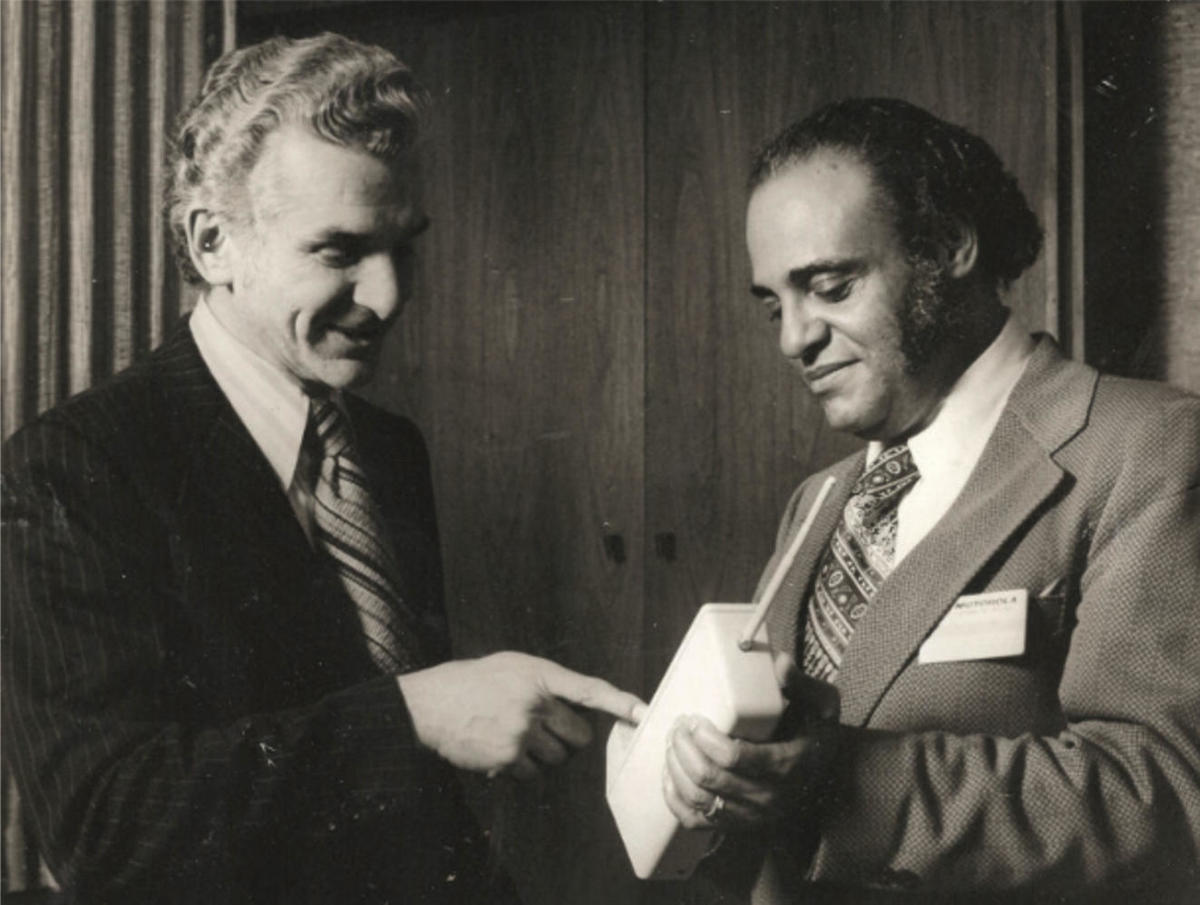

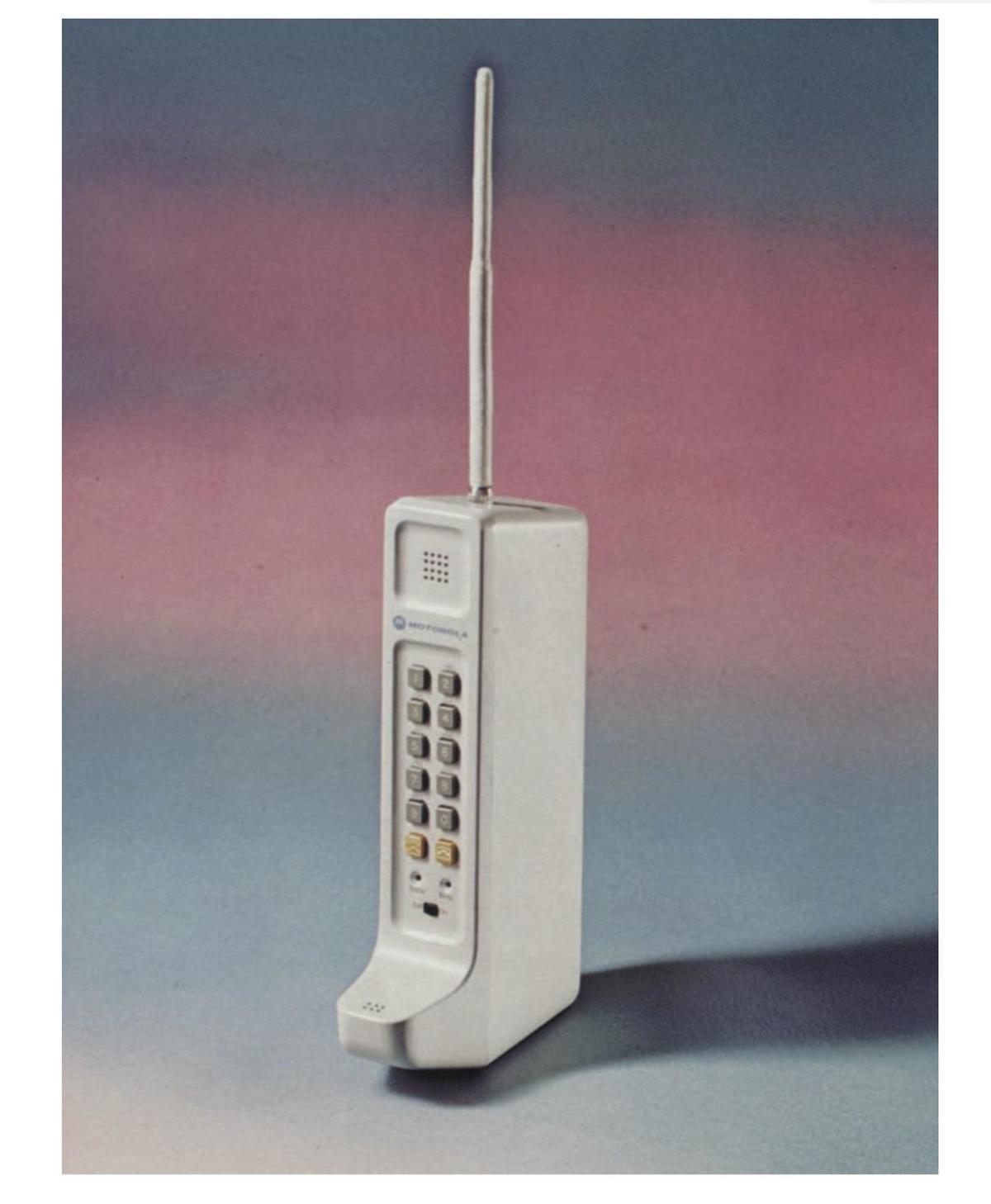

After three months of frantic effort, Cooper and team produced what must be one of the most beautiful prototypes ever created, the DynaTAC, for dynamic total-area coverage, the world’s first cell phone.

Motorola, Inc., Legacy Archives Collection. Reproduced with permission.

Hence, full-blown like the children of Zeus from the god’s head, after three months of frantic effort, Cooper and team produced what must be one of the most beautiful prototypes ever created, the DynaTAC, for “dynamic total-area coverage,” the world’s first cell phone. (The book includes, among many marvelous illustrations, plates from the archive showing the other designs, which included just about every “form factor” that would be later pursued, including flip phones and slider phones — all of this in 1973.)

In a scenario that blows away any demo since, Cooper made the fist cellular call on a New York City street outside the Hilton hotel for a reporter, calling one of his rivals at AT&T. Remember that when Steve Jobs made the first call on the iPhone, in January of 2007, it was to his design guru, Jony Ive, sitting in the audience of the Moscone Center in San Francisco just a hundred feet or so from the stage. In Cooper’s case, his team had set up a dedicated base station on the nearby Burlington building to route calls from Cooper down on the sidewalk.

The incident is legendary, but reading Cooper describe all the details of that day in April, 1973, is riveting.

Cellular went live in select markets in 1983, a year before Ma Bell’s breakup, and Cooper, having realized he wasn’t really big company, executive suite material, moved on to found a fascinating list of startup companies that did cool things with cellular, including ArrayCom, a pioneer in the kinds of adaptive array technology that has become essential in cellular.

Moto lost its way, a topic Cooper touches on just briefly. The crux seems to be that Moto insisted analog would prevail in cellular. Nokia and Ericsson grabbed hold of the emerging digital cellular technology and proceeded to eat Moto’s lunch in handsets and infrastructure.

The back half of Cooper’s book is a pivot to talking about the future. It’s wonderful to hear how someone who helped to birth a new world now reflects on where it will go. He foresaw portability, but even Cooper didn’t anticipate the computing device that the smartphone would become.

Cooper is exhilarated by the future. Chapters describe the potential impact on education and health care, and Cooper has assiduously documented how the phone has already contributed in a major way to bringing people out of poverty. One of the surprising pluses of the book is that Cooper is not merely reflecting, he has gone back and done research to present stats on phone usage and economic impacts as any good reporter would do.

The final piece of the book is Cooper’s reflection on A.I. To the delight of those who might wish to merge with machines, and perhaps to the dismay of human nativists, Cooper is upbeat that in generations to come, the cell phone will be our personal point of interface with an “augmented” self, which he refers to as Human 3.0:

The augment is learning; it’s getting smarter and absorbing more information . Communication between the augment and the human becomes more complex, more detailed . In succeeding generations, the human and the augment’s AI develop their own private language, just as twins who grow up together learn to communicate in private ways that others cannot penetrate. […] An embedded fuel cell in the human body will power the communications processor and the AI. That may sound like it’s straight out of The Matrix, but it is almost certainly on the way.

Bracing stuff. These future prospects are all just sketches, but they are potent topics for thought.

What makes the book work through all the detail and the thrilling accounts is Cooper’s generous voice coming though. He concedes he is “an optimist.” But actually, it’s more than that. There is a spirit of gratitude that pervades the reflections that is endearing, gratitude toward his colleagues, his fellow engineers, gratitude toward chance for presenting opportunities, and even generosity toward the big bad monopoly of AT&T that ultimately just couldn’t get out of its own way.

Cooper doesn’t harp on it, but we’re aware there is a connection in his concept of portability, and the facts of Cooper’s immigrant heritage. His mother, Mindel Bassovsky, fled the town of Pavloch in the Ukraine to Belgium in 1921 via horse-drawn cart to escape the pogroms being committed by Cossacks. She met and married another Ukrainian, Arthur Kuperman, and they settled in Canada. The early childhood of Cooper was one of constantly moving between Canada and the U.S. as his entrepreneurial parents pursued various businesses.

Not so surprising, then, his observation that “people are inherently fundamentally mobile.”

That a child of people on the move should find his way though brilliance and pluck and also through chance to creating something that might lift people out of poverty is one of those curves in the shape of history that is astounding. You can’t make this stuff up.

As Cooper humbly reflects,

Creation of the handheld cell phone was, technically speaking, inevitable . The cell phone—as a commercial, consumer product—would still have happened without the contributions of me and my colleagues at Motorola. But it would have taken longer, and it would have been quite different. Someone needed to nudge it forward into existence.

For anyone who’s a technology skeptic, the charm and grace in Cooper’s account may make you stop and reconsider. You might even linger on Cooper’s contention, toward the end of the book, that artificial intelligence will make us more human.

“Human 3.0, most likely, will be biological, but its biological structure will have been created by Human 2.0 rather than evolving over eons,” he writes. “And it will have more humanity than any human ever had.”