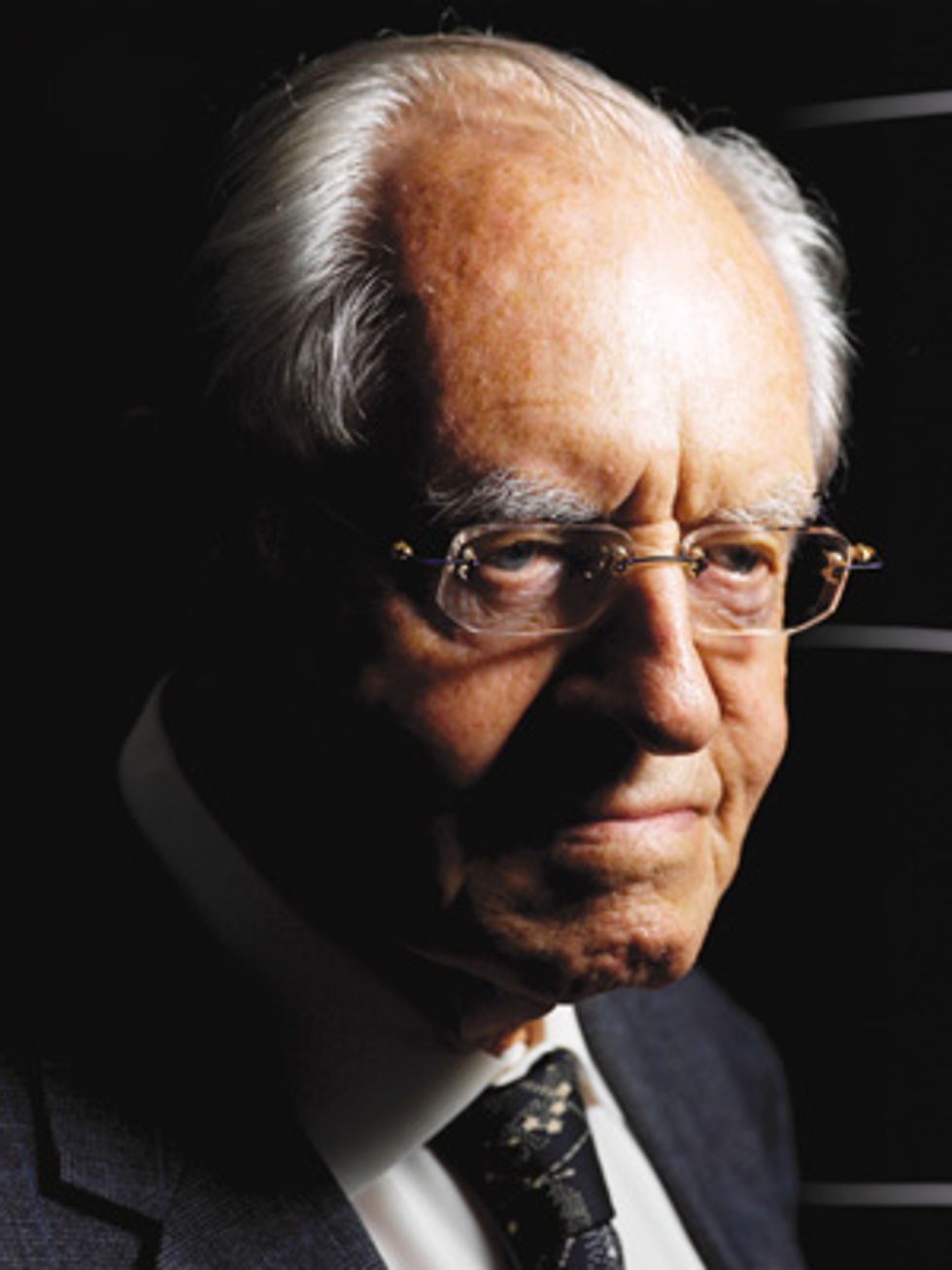

Invention and Inventors: In Paris, shortly after World War II, two German scientists, Herbert Mataré (above) and Heinrich Welker, invented the “tran- sistron,” a solid-state amplifier remark- ably similar to the transistor developed by Bell Telephone Laboratories at about the same time. In this X-ray image of a commercial transistron built in the early 1950s, two closely spaced metal point contacts, one from each end, touch the surface of a germanium sliver. A third electrode contacts the other side of the sliver. Mataré is now retired and living in Malibu, Calif.

Photo: Gusto Images

In late 1948, shortly after Bell Telephone Laboratories had announced the invention of the transistor, surprising reports began coming in from Europe. Two physicists from the German radar program, Herbert Mataré and Heinrich Welker, claimed to have invented a strikingly similar semiconductor device, which they called the transistron, while working at a Westinghouse subsidiary in Paris.

The resemblance between the two awkward contraptions was uncanny. In fact, they were almost identical! Just like the revolutionary Bell Labs device, dubbed the point-contact transistor, the transistron featured two closely spaced metal points poking into the surface of a narrow germanium sliver. The news from Paris was particularly troubling at Bell Labs, for its initial attempts to manufacture such a delicate gizmo were then running into severe difficulties with noise, stability, and uniformity.

So in May 1949, Bell Labs researcher Alan Holden made a sortie to Paris while visiting England, to snoop around the city and see the purported invention for himself. “This business of the French transistors would be hard to unravel, i.e., whether they developed them independently,” he confided in a 14 May letter to William B. Shockley, leader of the Bell Labs solid-state physics group. “As we arrived, they were transmitting to a little portable radio receiver outdoors from a transmitter indoors, which they said was modulated by a transistor.”

Four days later, France’s Secretary of Postes, Télégraphes et Téléphones (PTT), the ministry funding Mataré and Welker’s research, announced the invention of the transistron to the French press, lauding the pair’s achievement as a “brilliante réalisation de la recherche française.” Only four years after World War II had ended in Europe, a shining technological phoenix had miraculously risen from the still-smoldering ashes of the devastation.

“This PTT bunch in Paris seems very good to me,” Holden candidly admitted in his letter. “They have little groups in all sorts of rat holes, farm houses, cheese factories, and jails in the Paris suburbs. They are all young and eager.” And one of these small, aggressive research groups, holed up in a converted house in the nearby village of Aulnay-sous-Bois, had apparently come through spectacularly with what might well be the invention of the century—a semiconducting device that would spawn a massive new global industry of incalculable value. Or had it?

As was true for the Bell Labs transistor, invented by John Bardeen and Walter H. Brattain in December 1947, the technology that led to the transistron emerged from wartime research on semiconductor materials, which were sorely needed in radar receivers. In the European case, it was the German radar program that spawned the invention. Both Mataré and Welker played crucial roles in this crash R&D program, working at different ends of the war-torn country.

Mataré [see photo in “Transistor Twin”], who shared his remembrances from his home in Malibu, Calif., joined the German research effort in September 1939, just as Hitler’s mighty army rumbled across Poland. Having received the equivalent of a master’s degree in applied physics from Aachen Technical University, he began doing radar research at Telefunken AG’s labs in Berlin. There he developed techniques to suppress noise in superheterodyne mixers, which convert the high-frequency radar signals rebounding from radar targets into lower-frequency signals that can be manipulated more easily in electronic circuits. Based on this research, published in 1942, Mataré earned his doctorate from the Technical University of Berlin.

At the time, German radar systems operated at wavelengths as short as half a meter. But the systems could not work at shorter wavelengths, which would have been better able to discern smaller targets, like enemy aircraft. The problem was that the vacuum-tube diodes that rectified current in the early radar receivers could not function at the high frequencies involved. Their dimensions—especially the gap between the diode’s anode and cathode—were too large to cope with ultrashort, high-frequency waves. As a possible substitute, Mataré began experimenting on his own with solid-state crystal rectifiers similar to the “cat’s-whisker” detectors he had tinkered with as a teenager.