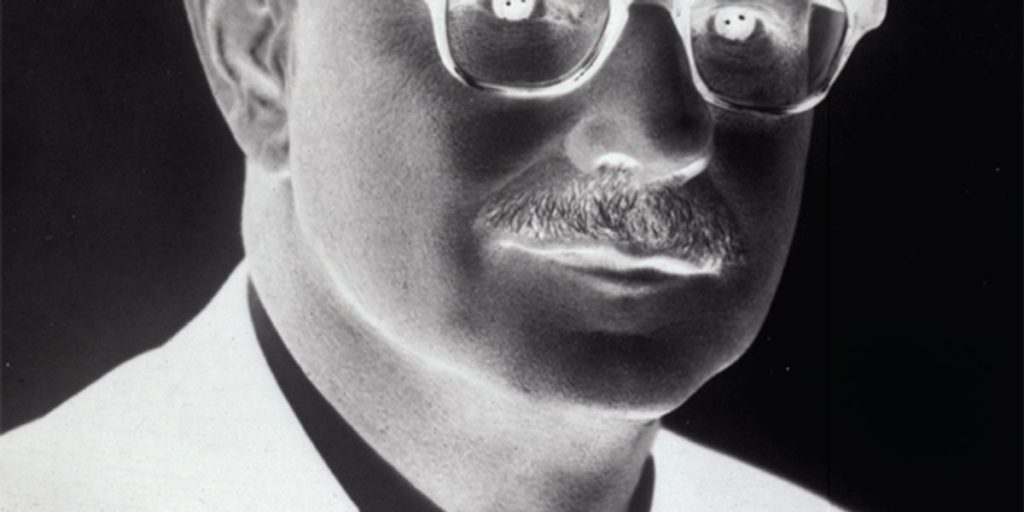

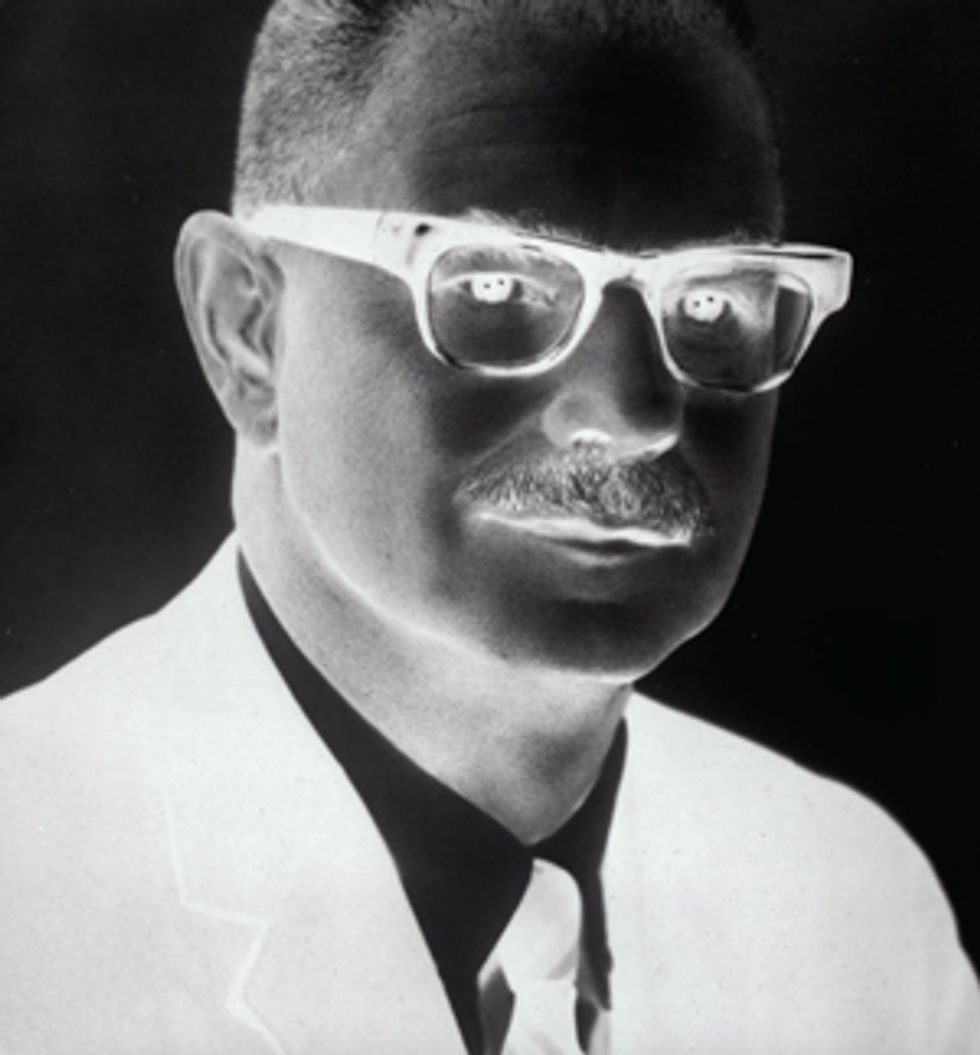

Flawed Hero: Jack A. Morton led Bell Labs’ effort to transform the transistor from a research curiosity into a commercial product. But his aversion to microchips would later cost AT&T dearly.

Photo: AT&T Archives and History Center

At 4:15 a.m. on 11 December 1971, firemen extinguishing an automobile blaze in the New Jersey hamlet of Neshanic Station were shocked to discover a badly charred body slumped face-down in the back seat. It proved to be the remains of Jack A. Morton, the vice president of electronic technology at Bell Telephone Laboratories, in Murray Hill, N.J. He had last been seen talking with two men at the nearby Neshanic Inn just before its 2 a.m. closing—about 100 meters from the abandoned railroad tracks where his flaming Volvo sports coupe was spotted. Local police quickly arrested and booked the men for murder.

This gruesome slaying ended the stellar career of the man who had led Bell Labs’ effort to transform the transistor from a promising but rickety laboratory gizmo into the sturdy, reliable commercial product that eventually revolutionized electronics. During the 1950s and 1960s, Bell Labs’ golden age, Morton served as quarterback of the device development team, making nearly all the key calls on which technologies to pursue and which to forgo. He was a bold, forceful, decisive manager who didn’t suffer fools gladly. And with some of the world’s most intelligent and innovative researchers working for him, he rarely had to.

Morton didn’t always make the right decisions, however. As one of his former colleagues observed, decisive leadership can easily become a flaw rather than a virtue [see photos, “Flawed Hero”]. On integrated circuits in particular, Morton exhibited serious blind spots that cost the parent phone company, AT&T, dearly—and may have contributed to its eventual dismemberment. But his untimely death meant that he would not be around to witness the consequences of his choices.

Like so many of the leading figures in the semiconductor industry—John Bardeen, Nick Holonyak, Jack Kilby, Robert Noyce—Jack Morton was born and raised in America’s pragmatic heartland. After growing up in St. Louis, he matriculated at Wayne University, in Detroit, where he was a straight-A electrical engineering major as well as quarterback of the football team. He was avidly pursuing graduate work in the discipline at the University of Michigan, intent on an academic career, when Bell Labs research director Mervin Kelly happened to visit in 1936. Kelly offered the promising young engineer an R&D position. Morton accepted, planning to pursue a Ph.D. in physics at Columbia University simultaneously. At Bell Labs, he started the same year as John Pierce, who would go on to pioneer satellite communications; Claude Shannon, who would lay the foundations for information theory; and William Shockley, who would share the Nobel Prize for inventing the transistor.

A visionary firebrand, Kelly had directed vacuum-tube R&D at the Labs [see photos, “Early Promise”]. He was keenly aware of the limitations of the bulky, power-hungry devices and the problems with the electromechanical relays then used as switches to connect phone calls throughout the Bell System. He envisioned a future when this switching would be done completely by electronic means based on the solid-state devices that were beginning to find applications in the late 1930s. To realize his dream, he hired the best scientists and engineers he could cajole into working in an industrial laboratory.

World War II put the project on hold. Kelly played a major wartime role, heading up radar development at Bell Labs and the Western Electric Co., AT&T’s manufacturing arm. Morton, too, did important military work. Having plunged into the intricacies of microwave circuit engineering just before the war, he helped design a microwave amplifier circuit that extended the range of radar systems and gave Allied forces in the Pacific a key advantage.

After the war, Morton developed a peanut-size vacuum triode that could amplify microwave signals. This triode served at the heart of the transcontinental microwave relay system that AT&T began building during the late 1940s, and it continued to be used in this capacity for decades, permitting coast-to-coast transmission of television signals.